A New Proxy Core, Sans I/O

19 Dec 2020, Maximilian Hils

I gave a talk introducing our then new — now old — proxy core at the Honeynet Workshop 2014. It didn’t age too badly, but it’s definitely outdated now. :-)

The upcoming release of mitmproxy 7 will feature a completely new I/O-free proxy core. In this post, I will go into the technical details and architectural changes coming up.

As the result of an effort that started in 2016, we are transitioning to a new proxy core rewritten from scratch. This fixes some longstanding issues, but most importantly allows us to deliver a much more robust mitmproxy once the initial teething troubles have been sorted out. This post sheds the light on the technical aspects of this change. We will start with a short trip down the memory lane to illustrate some problems with traditional blocking I/O implementations and then take a close look at the new I/O-free protocol pattern.

Backstory: Why I/O is no fun.

When I started building out mitmproxy’s current proxy core in ~2014, we opted for a fairly traditional design where

each connection is handled by a separate thread. Whenever a client connects, we spawn a new thread and let that thread

handle everything. This model has some nice properties: Clients generally don’t get into the way of each other, threads

are generally cheap enough for our purposes, and we can just block and wait for data!

Python’s socket.makefile

makes that particularly handy:

def read_request(conn: socket.socket):

f = conn.makefile()

# the next two operations may take a while,

# but other threads can work in the meantime!

headers = read_headers(f)

request_body = f.read(int(headers["content_length"]))

...

This produces code that’s easy to read and pretty straightforward to follow. Unfortunately, things get more tricky once we consider that our proxy server not only has a client connection, but also an upstream connection to the target server. For HTTP/1, we can still handle that in the same thread as we either read the request from the client or the response from the server, but not both at the same time. However, a potential issue here is that we don’t detect a disconnecting client while reading the response from the server. That can be ignored most of the time, but becomes rather annoying if the client started multiple large file downloads. Again there are some workarounds (like mitmproxy’s HTTP message body streaming, or explicit body size limits), but none of them are particularly satisfying.

Things get much more tricky when we take a look at HTTP/2, where we deal with multiple requests and responses in one

connection happening all at the same time. Our only way out is to either spawn more threads or do I/O multiplexing

using select() or other operating system APIs. While this sounds

promising, it isn’t all that simple. Once you start with multiplexing, you cannot block at all, or everything else

comes to a halt: We can’t wait for the next newline character to arrive because other requests need to be processed at

the same time. Our request-reading code from above becomes a little bit longer:

while True:

# Ask the OS for all connections where we have data waiting to be read.

ready_conn, _, _ = select.select(connections, (), (), timeout)

for conn in ready_conn:

if conn == client_conn and client_state == "read-request-headers":

client_conn_buffer += f.read(4096)

if b"\r\n\r\n" in client_conn_buffer:

... # handle receipt of complete HTTP headers

... # handle other states

This increase in complexity may look bad, but one could also argue that we have just made all potential race conditions more explicit, which is a good thing. We can conceivably isolate the complexity of protocol parsing into a seperate module or reuse existing libraries such as the excellent hyper-h2, h11, or wsproto.

Unfortunately, there is another major catch in our approach: Not only do our sockets block, but also mitmproxy itself

can block! For example, a user may intercept a request and modify it before sending it to the destination server.

We obviously do need to wait for this to finish, but handling these events does not fit into our select()-based loop at all!

Continuing the example from above:

if b"\r\n\r\n" in client_conn_buffer:

flow = parse_headers(client_conn_buffer)

mitmproxy_event("requestheaders", flow) # dang, this blocks!

...

The idea of non-blocking I/O is promising, but there was no easy fix this particular issue in our old core and we had to go back to threads. This naturally produced a vast array of hard-to-test race conditions which @Kriechi, our HTTP/2 specialist, diligently reproduced and debugged.

Sans I/O

While a non-blocking model did not work for our old proxy architecture, we did see the promise of having synchronous — thread-free — code that describes our proxying logic. The lack of threading race conditions leads to simpler code that can be tested reliably and is more robust. The new proxy core fulfills this mission and is implemented entirely as synchronous functions returning synchronous results. It never blocks or waits for any form of input.

Next, I will give a small overview of this system.

Events and Commands

The major abstraction used by mitmproxy’s new proxy core is to translate bytes received from the network into “events”.

A client opening a connection to the proxy is translated into a Start event; sending data is modeled as

a DataReceived event; a peer closing a connection is a ConnectionClosed event. These events are then fed

into .handle_event(event), which returns a list of commands1. The returned commands are instructions for the

I/O-handling server part: They can be simple network operations on existing sockets (SendData, CloseConnection),

instructions to open a new socket (OpenConnection), or instructions to pass an event to the rest of mitmproxy (Hook)

. The completion of such a hook (for example, the user has resumed an intercepted message) is also translated into a

regular event (HookReply) and handled the same way as other I/O events. This solves our problem that mitmproxy itself

can block!

With a bit of syntactic sugar, we can assemble “playbooks“ that describe the expected commands for a given sequence of events:

# >>: Events go into the proxy core

# <<: Commands come out of the proxy core

assert (

Playbook(http_layer)

>> Start()

>> DataReceived(client, b"GET http://example.com/foo?hello=1 HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n")

<< HttpRequestHeadersHook(flow)

>> reply()

<< HttpRequestHook(flow)

>> reply()

<< OpenConnection(server)

>> reply(err=None)

<< SendData(server, b"GET /foo?hello=1 HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n")

>> DataReceived(server, b"HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nContent-Length: 12\r\n\r\nHello World!")

... # response events

<< SendData(client, b"HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nContent-Length: 12\r\n\r\nHello World!")

)

Note how this seamlessly intertwines events from multiple network connections and mitmproxy itself. This fundamentally changes the way we are able to test mitmproxy. Testing complex protocol interactions previously required a delicate orchestration of client, proxy, and server connections. With sans-io, we can instead express arbitrary scenarios as a deterministic sequence of commands and events.

Layers

A concept we carry over from the old implementation is that of layers. When a client connects to mitmproxy, it will

communicate with the I/O server, which encapsulates all asynchronous activity. This component essentially performs the

select() part of the old core and translates all network activity into events. These are then passed to the outermost

protocol layer, which depicts the proxy mode (reverse, transparent, SOCKS, or HTTP proxy mode). From there,

events usually travel through a series of layers before they hit “the core business logic“.

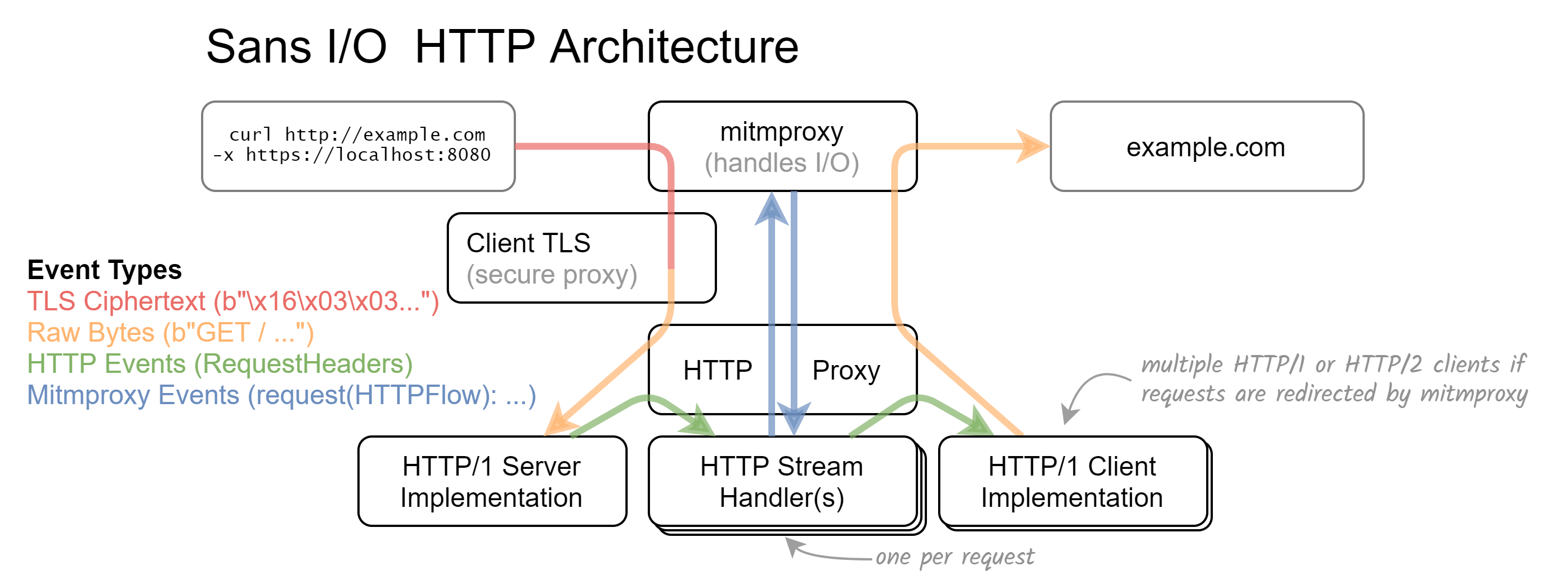

mitmproxy’s layered proxy core. In this specific configuration, mitmproxy is run as a Secure Web Proxy where the client establishes a TLS connection with the proxy first. This protects possible plaintext communication between client and proxy.

In the example above, we receive encrypted data on the wire. The client TLS layer then takes those bytes, feeds them

into OpenSSL, and creates a new DataReceived event with the decrypted plaintext. This is passed to the HTTP/1 server

implementation, where it is parsed the same way a plaintext connection would be. The HTTP proxy layer — whose main

task is to coordinate all sublayers — then passes the interpreted results to the correct HTTP stream handler. This

layer handles the lifecycle of a single HTTP request/response pair, emits event hooks for the rest of mitmproxy, and

potentially creates further child layers (for example to handle WebSocket connections).

While this may seem tedious, it enables a clear separation of concerns. For example, the HTTP stream layer depicted above can now deal with both HTTP/1 and HTTP/2 peers on either end. HTTP version interoperability may seem like an insignificant detail, but allows us to negotiate HTTP/2 with a client without connecting to the upstream server first (which we would otherwise need to do to check for HTTP/2 support). We can now replay HTTP/2 responses from mitmproxy without ever connecting upstream!

Wrap-Up

There are many more features that I have not touched upon or only mentioned briefly here. For example, the use of OpenSSL’s memory BIO finally allows us to support TLS-over-TLS, a requirement to intercept traffic in Secure Web Proxies. Our proxy core is now fuzzed not only with random bytes as input, but also with mutated event orders in playbooks. While our new architecture doesn’t scale for high-performance applications (in particular, we don’t model backpressure), we are very happy with the design decisions we have made. I hope that I could convey some of the excitement and that you will enjoy the next mitmproxy release!

Next Steps

Our sans-io effort started in 2016, this week we have finally merged 195 commits, added 10k lines of code and deleted even more than that. We are obviously very excited, and please be forgiving if we introduced a bug or two somewhere. If you would like to support our effort, please help test the latest snapshots builds! A few features from the old proxy core also did not make it to the new implementation yet. Please let us know what we should focus on in #4348.

Acknowledgments

This effort certainly wouldn’t have been possible without the excellent sans-io libraries we depend on. A particular thank you goes to Cory Benfield, Benno Rice, Philip Jones, Nathaniel J. Smith, Thomas Kriechbaumer, and all other contributors who help maintain hyper-h2, wsproto, and h11. Some explanations in this post were heavily inspired by Brett Cannon’s sans-io website.

-

Many other sans-io implementations refer to what we call “commands“ as “events”. For example, wsproto has a

.receive_bytesmethod which emits events. In mitmproxy’s terminology, “events” (triggered externally) go into the proxy, which then returns (deterministic) “commands“. ↩︎